Twenty-five years of risk-reducing mastectomies and immediate breast reconstruction—lessons learned from a single institution

Introduction

“One day my doctor called to inform me that the tests showed that I had inherited a very high risk for breast cancer. I was also told that removing both breasts would almost exclude the risk of getting breast cancer. Later I had a referral to the plastic surgeons, who informed me about the procedure, and I chose to have the operation. I was not mentally prepared, although the breasts had no positive impact on my life except for breast feeding. After 20 years, I still have less sensation in my new breasts and feel uncomfortable in intimate situations. The operation has negatively affected my sexuality. Nevertheless, I do not regret having had the operation, and my anxiety of getting breast cancer is almost gone”. These reflections originate from a series of prospective and retrospective studies from asymptomatic women with an increased risk for breast cancer treated at the Karolinska University Hospital Sweden from 1994–2018 by our collaborative group.

Before the cloning of the two highly penetrant tumor suppressor genes, BRCA1 & BRCA2, women from families at high risk were identified through a clinical and laboratory collaboration with geneticists and oncogeneticists (with molecular workup). They were offered regular surveillance or risk-reducing surgery of the breasts and ovaries. The Mayo studies that had been published showed a more than 90% risk reduction after bilateral risk-reducing breast mastectomy (BRRM) in asymptomatic high-risk individuals (1). After cloning the genes, these findings were corroborated by the Mayo group and others (2,3). Other studies showed a higher incidence of breast cancer in women who chose surveillance over BRRM (4). Initially, however, this irrevocable surgical procedure was considered controversial, with various rates of uptake (5).

At the Karolinska University Hospital, a multidisciplinary group of specialists and nurses was founded in 1999 with a psychologist attached to the team. A contact nurse served as a liaison between the different specialists and the patient. Regular team conferences were established, and all cases identified either by mutation screening or by risk assessment instruments, initially by using Claus tables and later by BOADICEA, were discussed (6,7). Women opting for surgery were interviewed, and prospective trials started to evaluate complications and health-related quality of life before and after the surgeries. The aim of this paper is to describe the significant experiences and developments over more than 25 years and after approximately 700 procedures. During the last 5 years, approximately 50 women per year have been operated at Karolinska.

Surveillance program

Initially, both women who were found to be at an inherited increased risk for breast and ovarian cancer and those who had been diagnosed with breast cancer were offered to participate in a surveillance program with regular controls, including (I) clinical breast examination, (II) mammogram and (III) ultrasound at regular intervals. To assess the sensitivity and specificity of the different modalities, 632 women at high risk from the hereditary cancer clinics in Stockholm were followed from 2002–2012. Any women with an estimated high risk, proven mutation carriers, and women with a history of breast or ovarian cancer who were five years disease free and had a normal mammogram one-year pre-study were eligible for inclusion. All screening modalities were blinded, coded and assessed. After 5 screening rounds, the clinical breast exam was deemed insufficient and not relevant as a screening modality. Ultrasound was found to be superior to mammography. When MRI became clinically available, it was added to the surveillance program. The screening program has thereafter been modified. Currently, the recommendations from the hereditary cancer clinic for women at elevated risk for breast cancer state that asymptomatic individuals with a known mutation in the BRCA1, BRCA2, PALPB2, CHEK2 or ATM gene should be offered imaging with mammography and ultrasound at six-month intervals and yearly MRI. Carriers below the age of 30 undergo ultrasound and MRI at the same intervals. Those with an intermediate life time risk of 20–29% according to BOADICEA and with no proven mutation are offered yearly mammography and ultrasound (8).

Preoperative counselling

From the beginning of the program, it was obvious that emotional support to the women at high risk was needed and that individualized preoperative information regarding surgical options had to be given. Over time, the information has become structured and is addressed in a stepwise fashion, as the women’s psychological readiness for understanding the risk and the consequences of the surgical procedure varies. From the start, the multidisciplinary team included a psychologist, with whom all women were offered contact. The psychologist assessed the expectations of the women and their psychosocial situations. Communication regarding risk was done by professional genetic counsellors. All cases were discussed in the multidisciplinary team before risk-reducing surgery was offered, after a unanimous decision. At a first joint appointment with the breast surgeon and plastic surgeon, women were informed about the possibility of BRRM, and meticulous information about risks and benefits with the procedure was given. Patient photographs pre- and postoperatively were shown to serve as a model for what could be expected in their case. A contact nurse was the core manager of the team and was readily available for any woman who needed more information or support. This structured approach with a contact nurse as a navigator for the patient and the team is still our modus operandi. All women are seen in the hereditary cancer clinic once after genetic testing and workup for information regarding risk estimation, mutation analysis (if done) and information about self-examination. If any breast symptoms are present, they are referred to a breast unit. Discussion regarding BRRM is undertaken if the estimated life time risk is beyond 24% and the woman has proven mutation carrier status. All women eligible for surgery are discussed at regular multidisciplinary conferences, after which they are offered a first surgical appointment with a plastic surgeon to discuss possible reconstructive options. Very rarely, a woman opts to undergo mastectomy only.

Technical aspects of BRRM

The team approach for mastectomy and breast reconstruction has prevailed since the start. Breast surgeons and plastic surgeons perform the mastectomy and reconstruction as one team, except in cases where autologous flaps are employed with microsurgical techniques. Extreme care to remove all breast tissue has always been a cornerstone, sometimes with the cost of very thin skin flaps, 0.5 to 1 cm thickness. Still, no mastectomy can be sure to be one hundred percent complete, an important fact conveyed to every woman undergoing BRRM.

Mastectomy

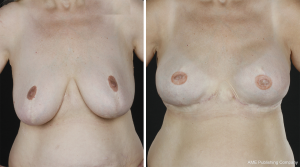

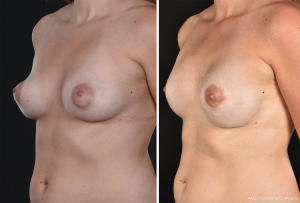

Conventional mastectomy incisions were used in the beginning, and the nipple areola complex (NAC) was removed. The nipples were re-grafted after securing a specimen from the base. If premalignant or malignant features were found in the nipple base biopsy, the nipple was later removed. We have not at any time used frozen sections (Figure 1).

Satisfactory results were obtained in the majority, but graft failure of the nipple sometimes occurred, and the reconstructed and tattooed NAC would then have an unnatural appearance. Gradually, more skin-saving NAC-sparing procedures came into use, and an upper areola incision, sometimes Omega-type or with a lateral extension, became the standard technique for women with small to average-sized breasts. In cases of larger breast volumes or skin excess, Wise pattern incisions were performed (Figure 2). Nipple-sparing mastectomy incisions close to the areola may result in scars that retract the NAC from its natural position. They may also impair the blood supply and thus increase the risk of necrosis of the areola or depigmentation (Figure 3). At present, most BRRMs are performed through inframammary incisions, which seem to give the most natural breast appearance with a less obvious scar (Figure 4). This technique is technically more challenging, especially for reaching the axillary tail. In a medium-sized breast, a lateral lazy-S incision may allow for a technically easier mastectomy.

Reconstruction

Expander implants have been the foremost commonly used reconstruction mode with a submuscular placement and total muscular coverage by the pectoralis major and serratus muscle. Tattooing of the areolae and removal of the filling ports have been done as outpatient procedures under local anesthesia. Revision surgeries have been frequent due to unanticipated procedures such as capsular contracture, the need for adjustment of implant position and size or implant loss due to infection or flap necrosis. In a national audit including 223 Swedish women who had undergone BRRM from 1995 to 2005 with a mean follow-up of 6.6 years, the implant loss was 10 percent, and 64 percent of the women underwent unanticipated secondary surgeries (9).

At present, submuscular placement of microtextured anatomical implants with muscle cover, but when possible only serratus anterior fascia for lateral cover, as a one-stage procedure has become the standard technique for breast sizes up to an estimated breast volume of approximately 300–350 cc. This often results in high patient satisfaction and is cost-saving. Permanent expandable anatomical implants are used for larger and/or ptotic breasts with excess skin and continue to be a greater surgical challenge with a higher risk for complications. Combining the Wise pattern incision with the use an autologous dermal sling can improve the aesthetic results because the NAC can sometimes be saved and repositioned on a dermal pedicle (Figure 5). We rarely use acellular dermal matrices or meshes. The technique has been evaluated by our unit in a recently published randomized trial for breast cancer patients using a porcine ADM, showing more adverse complications associated with the use of ADM (10). We have not used pre-pectoral implant positioning in BRRM patients because the long-term result of this reconstruction is still unclear, and the technique also includes the use of a large piece of ADM. Breast reconstruction using implants in young and middle-aged women is a procedure that will necessitate future surgery because of capsule formation and bodily changes in the individual. This is important to address in the preoperative information given.

Autologous reconstruction

In selected cases, autologous reconstruction is done, mainly using deep inferior epigastric perforator (DIEP) flaps. This technique is highly preferred for women with previous radiotherapy to the chest wall, as implant reconstruction often gives less satisfactory results due to capsular contracture (Figure 6A,B). In 2018, 13 percent of the BRRMs at the Karolinska were autologous, and the demand is increasing. Autologous fat transplantation has been used with good results in women with subcutaneous irregularities after mastectomy and reconstruction but often requires several sessions (11).

Management of postoperative pain

The placement of an implant behind the pectoralis major muscle causes pain and discomfort with unsatisfactory outcomes using opioids and paracetamol only. In a series of studies including randomized trials, it was concluded that self-administered opioids were not safe during the postoperative period and in the long term the addition of long-acting local anesthetics was superior and effective in pain control and in reducing opioid consumption (12). The addition of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) further improved pain control, but when used continuously with patient-controlled analgesia (PCA pumps), more bleeding occurred (13). For almost 20 years, indwelling catheters with solely ropivacaine became routine and further reduced the opioid consumption (14). Currently, our pain management regime includes the pectoralis and serratus blocks administered perioperatively by the surgical team, gabapentin for 2–3 days during the peri- and postoperative period, and paracetamol and coxibs. Opioids are used cautiously due to side effects and are rarely needed after the first few days. Hospital stay has been reduced from 5–7 to 2–3 days.

Safety of procedure and regional differences

The goal of BRRM is that the patient be saved from breast cancer. A national inventory commissioned by the Swedish Oncogenetic Group invited all participating university units to contribute clinical information of high-risk and proven mutation carriers who had undergone BRRM. From 1995–2005, 223 cases were reported from eight Swedish units. All cases had an increased risk of breast cancer proven by mutation screen or by risk assessment analyses. The majority were done in 2/8 units, and patients from Karolinska dominated. One case of disseminated cancer was reported during the follow up, and very few serious complications occurred. Implants were predominantly used. At that time, only one unit performed autologous reconstructions (9).

Quality-of-life studies and patient-reported outcomes after BRRM

The risk of having breast cancer can be effectively reduced by RRM, and a recently published Cochrane analysis confirms this, though prospective studies are warranted (15). The medical community initially raised concerns over this radical approach. The “Angelina Jolie effect” later had a massive impact on mainly consumer-driven requests for genetic testing and increased public knowledge about RRM (16,17). How the surgery affects the individual who has undergone this radical approach and experiences her changed body every day was equally important to evaluate. Several quality-of-life studies with patients’ self-reported outcomes and experiences (PROM and PREM) were performed. Having a clinical and academic psychologist on the team facilitated the prospective and retrospective trials from the start of the structured care process and onwards (18-23). Both quantitative and qualitative studies of these women in the short and long term contributed knowledge to the clinical management and nursing, as it became evident that information was lacking and that women needed time to decide and to mourn the breast loss. Further, it was important to maintain realistic expectations of the procedure. Findings from our studies have been corroborated by others: women are less anxious after BRRM, and their QOL is not affected (24). When asked specifically about bodily symptoms, women report loss of sensibility in the short and long term, a sense of being uncomfortable in intimate situations, loss of sensitivity in the breast, negatively affecting sexual pleasure after BRRM, and the texture of the breast being hard (20,25-28). These findings are also in line with other studies (29-31). However, we have not encountered patients who strongly regret their decision to undergo BRRM, and in general, patients are satisfied with the procedure.

Summary

During a 25-year period of managing this challenging asymptomatic but psychologically affected patient group, several important steps have been taken. From the patients, a wealth of knowledge has emerged that has enabled adjustments in nursing. Technical advances in devices and surgical performance skills together with experience have led to a more tailored approach. The hospital stay has almost halved, and most patients resume work after four to six weeks. Revision surgeries over the long term due to capsule formation and patients’ bodily changes are necessary. Risk-reducing mastectomy is a procedure limited to a restricted group of patients at a substantially high risk of getting breast cancer who should be well informed and counselled and managed by a dedicated team that also audits the results (Table 1).

Table 1

| Indications for RRM—strict and according to guidelines for women at high risk for breast cancer. Discussed in multidisciplinary teams |

| Preoperative assessment and information—assure that patients are well informed and evaluated regarding expectations of the procedure, including their psychosocial situation. RRM is not an emergency procedure |

| Perioperative management—use a standardized pain regimen, use opioids sparingly |

| Surgical and reconstructive technique—tailored to the native breast volume and shape. Perform a safe mastectomy to assure maximum glandular excision and avoidance of flap necrosis. Inframammary incisions preferred but technically more challenging. Provide the possibility of both implants and autologous reconstructive techniques. Should be performed by a dedicated surgical-reconstructive team |

| Postoperatively—audit results |

RRM, risk-reducing mastectomy.

Acknowledgments

All patients who accepted inclusion in the studies; the current and previous team: Brita Arver, Edward Azevedo, Lucy Bai, Yvonne Brandberg, Peter Emanuelsson, Hanna Fredholm, Ann Linden, Jakob Lagergren, Annelie Liljegren, Svetlana Baljika-Lagercrantz, Helena Poska, Anne Kinhult-Ståhlbom and Marie Wickman.

Funding: None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/abs.2019.11.01). KS serves as an unpaid editorial board member of Annals of Breast Surgery from Nov 2018 to Oct 2020. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Hartmann LC, Schaid DJ, Woods JE, et al. Efficacy of bilateral prophylactic mastectomy in women with a family history of breast cancer. N Engl J Med 1999;340:77-84. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hartmann LC, Sellers TA, Schaid DJ, et al. Efficacy of bilateral prophylactic mastectomy in BRCA1 and BRCA2 gene mutation carriers. J Natl Cancer Inst 2001;93:1633-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rebbeck TR, Friebel T, Lynch HT, et al. Bilateral prophylactic mastectomy reduces breast cancer risk in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers: the PROSE Study Group. J Clin Oncol 2004;22:1055-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Meijers-Heijboer H, van Geel B, van Putten WL, et al. Breast cancer after prophylactic bilateral mastectomy in women with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation. N Engl J Med 2001;345:159-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Metcalfe KA, Birenbaum-Carmeli D, Lubinski J, et al. International variation in rates of uptake of preventive options in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. Int J Cancer 2008;122:2017-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Antoniou AC, Pharoah PP, Smith P, et al. The BOADICEA model of genetic susceptibility to breast and ovarian cancer. Br J Cancer 2004;91:1580-90. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Claus EB, Risch N, Thompson WD. Autosomal dominant inheritance of early-onset breast cancer. Implications for risk prediction. Cancer 1994;73:643-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Liljegren A, von Wachenfeldt A, Azavedo E, et al. Prospective blinded surveillance screening of Swedish women with increased hereditary risk of breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2018;168:655-66. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Arver B, Isaksson K, Atterhem H, et al. Bilateral prophylactic mastectomy in Swedish women at high risk of breast cancer: a national survey. Ann Surg 2011;253:1147-54. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lohmander F, Lagergren J, Roy PG, et al. Implant Based Breast Reconstruction With Acellular Dermal Matrix: Safety Data From an Open-label, Multicenter, Randomized, Controlled Trial in the Setting of Breast Cancer Treatment. Ann Surg 2019;269:836-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schultz I, Lindegren A, Wickman M. Improved shape and consistency after lipofilling of the breast: patients' evaluation of the outcome. J Plast Surg Hand Surg 2012;46:85-90. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Legeby M, Segerdahl M, Sandelin K, et al. Immediate reconstruction in breast cancer surgery requires intensive post-operative pain treatment but the effects of axillary dissection may be more predictive of chronic pain. Breast 2002;11:156-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Legeby M, Sandelin K, Wickman M, et al. Analgesic efficacy of diclofenac in combination with morphine and paracetamol after mastectomy and immediate breast reconstruction. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2005;49:1360-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Turan Z, Sandelin K. Local infiltration of anaesthesia with subpectoral indwelling catheters after immediate breast reconstruction with implants: a pilot study. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg 2006;40:136-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Carbine NE, Lostumbo L, Wallace J, et al. Risk-reducing mastectomy for the prevention of primary breast cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2018;4:CD002748 [PubMed]

- Evans DG, Wisely J, Clancy T, et al. Longer term effects of the Angelina Jolie effect: increased risk-reducing mastectomy rates in BRCA carriers and other high-risk women. Breast Cancer Res 2015;17:143. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Liede A, Cai M, Crouter TF, et al. Risk-reducing mastectomy rates in the US: a closer examination of the Angelina Jolie effect. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2018;171:435-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Arver B, Haegermark A, Platten U, et al. Evaluation of psychosocial effects of pre-symptomatic testing for breast/ovarian and colon cancer pre-disposing genes: a 12-month follow-up. Fam Cancer 2004;3:109-16. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Brandberg Y, Arver B, Lindblom A, et al. Preoperative psychological reactions and quality of life among women with an increased risk of breast cancer who are considering a prophylactic mastectomy. Eur J Cancer 2004;40:365-74. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Brandberg Y, Sandelin K, Erikson S, et al. Psychological reactions, quality of life, and body image after bilateral prophylactic mastectomy in women at high risk for breast cancer: a prospective 1-year follow-up study. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:3943-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Metcalfe KA, Esplen MJ, Goel V, et al. Predictors of quality of life in women with a bilateral prophylactic mastectomy. Breast J 2005;11:65-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tercyak KP, Peshkin BN, Brogan BM, et al. Quality of life after contralateral prophylactic mastectomy in newly diagnosed high-risk breast cancer patients who underwent BRCA1/2 gene testing. J Clin Oncol 2007;25:285-91. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wasteson E, Sandelin K, Brandberg Y, et al. High satisfaction rate ten years after bilateral prophylactic mastectomy - a longitudinal study. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2011;20:508-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Isern AE, Tengrup I, Loman N, et al. Aesthetic outcome, patient satisfaction, and health-related quality of life in women at high risk undergoing prophylactic mastectomy and immediate breast reconstruction. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 2008;61:1177-87. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bai L, Arver B, Johansson H, et al. Body image problems in women with and without breast cancer 6-20 years after bilateral risk-reducing surgery - A prospective follow-up study. Breast 2019;44:120-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gahm J, Edsander-Nord A, Jurell G, et al. No differences in aesthetic outcome or patient satisfaction between anatomically shaped and round expandable implants in bilateral breast reconstructions: a randomized study. Plast Reconstr Surg 2010;126:1419-27. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gahm J, Hansson P, Brandberg Y, et al. Breast sensibility after bilateral risk-reducing mastectomy and immediate breast reconstruction: a prospective study. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 2013;66:1521-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gahm J, Jurell G, Edsander-Nord A, et al. Patient satisfaction with aesthetic outcome after bilateral prophylactic mastectomy and immediate reconstruction with implants. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 2010;63:332-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dikmans REG, van de Grift TC, Bouman MB, et al. Sexuality, a topic that surgeons should discuss with women before risk-reducing mastectomy and breast reconstruction. Breast 2019;43:120-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Glassey R, Ives A, Saunders C, et al. Decision making, psychological wellbeing and psychosocial outcomes for high risk women who choose to undergo bilateral prophylactic mastectomy - A review of the literature. Breast 2016;28:130-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Matloff ET, Barnett RE, Bober SL. Unraveling the next chapter: sexual development, body image, and sexual functioning in female BRCA carriers. Cancer J 2009;15:15-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Sandelin K, Gahm J, Schultz I. Twenty-five years of risk-reducing mastectomies and immediate breast reconstruction—lessons learned from a single institution. Ann Breast Surg 2019;3:28.