Postoperative dermatologic sequelae of breast cancer in women: a narrative review of the literature

Introduction

In 2020, breast cancer was the world’s most prevalent cancer (1). Surgery remains the primary treatment for most breast cancers and more patients are electing to receive reconstruction in recent years (1,2). With scientific advances and developments in operative technique, cancer therapy can be personalized. In recent decades, traditional mastectomy has been supplemented with breast-conserving therapies, sentinel lymph node biopsy, lymph node dissection (3), as well as implant, autologous tissue, and nipple-areola complex reconstruction (4).

Despite the global burden of breast cancer and ever-evolving advancement of surgical techniques, the existing literature is limited in its review of postoperative dermatologic sequelae in breast cancer patients (5). To address this gap, our review provides a complete reference, comprehensively detailing the current understanding of presentation, etiology, diagnosis, and management of dermatologic postsurgical and reconstructive sequelae in breast cancer patients. We also identify limits in knowledge of pathogenesis and treatments of such conditions, suggesting areas for needed further research. The condition identified herein are classified as inflammatory, infectious, or lymphedema-associated entities. We present this article in accordance with the Narrative Review reporting checklist (available at https://abs.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/abs-22-39/rc).

Methods

A PubMed and EMBASE search was conducted for articles published between inception of the database and September 2021 using a comprehensive list of terms in three main categories, combined using the AND operator: (I) breast cancer; (II) breast cancer surgery; and (III) skin disease (Table S1). Selection criteria was determined prior to review of articles and included studies describing post-surgical skin conditions, risk factors, pathogenesis, and treatments. Studies were excluded if they were not in English. The titles, abstracts, and full texts were reviewed by authors Y.K. and A.M. independently and were included based on selection criteria. Discrepancies were resolved through author consensus (Table 1).

Table 1

| Items | Specification |

|---|---|

| Date of search | August 20th 2021–September 6th 2021 |

| Databases and other sources searched | PubMed and EMBASE |

| Search terms used | Comprehensive list of terms in three main categories, combined using the AND operator: (I) breast cancer; (II) breast cancer surgery; and (III) skin disease (Table S1) |

| Timeframe | Inception of the database through September 2021 |

| Inclusion and exclusion criteria | All study types included if describing post-surgical skin conditions, risk factors, pathogenesis, and treatments. Studies were excluded if they were not in English |

| Selection process | Selection criteria was determined prior to review of articles. Y.K. and A.M. independently conducted the selection. Discrepancies were resolved through author consensus |

Discussion

Inflammatory

Pyoderma gangrenosum (PG)

PG is a rare neutrophilic ulcerative skin disease commonly associated with skin trauma through pathergy (6-8). Postoperative PG presents at the surgical incision site with erythema or sterile pustules rapidly progressing to skin ulceration with irregular, undermined, violaceous borders, and wound dehiscence with systemic symptoms including fever and leukocytosis in half of patients (6,9) (Figure 1). Breast PG characteristically spares the nipple/areola complex (6) which can differentiate PG from mimickers including infection (8). PG of the breast presents 4 days to 6 weeks postoperatively (8) and latency period is related to the extent of surgery, with larger procedures leading to a shorter disease onset (10). PG pathogenesis is still not well understood. Neutrophil chemotaxis dysregulation due to genetic factors, underlying disease, or cytokine release from trauma caused by surgery may be implicated (6,8,10,11).

Postoperative PG diagnosis is challenging because surgical wound and necrotizing soft tissue infections present similarly (6,12). Misdiagnosis may lead to unnecessary antibiotic therapy or surgical debridement, which exacerbates PG due to pathergy (6). Recently, PG diagnostic criteria were established (13), requiring one major criteria and at least four minor criteria to be satisfied for diagnosis (14) (Table 2). Skin biopsy (or skin obtained during debridement) should be sent for histology as well as bacterial, fungal and mycobacterial cultures to aid in ruling out infection (10). Skin biopsies to evaluate for PG should be obtained from the ulcer edge including ulcerated and intact skin. Other inflammatory, ulcerating dermatologic conditions which have been rarely reported postoperatively on the breast include pemphigus vulgaris (15), ulcerative necrobiosis lipoidica (16), and skin necrosis following methylene blue dye injection for sentinel node biopsy (17). These conditions may be distinguished from PG as pemphigus vulgaris frequently presents with mucocutaneous disease and can be definitively diagnosed via biopsy (15), necrobiosis lipoidica often presents first with a yellow atrophic plaque (16), and skin and fat necrosis lacks the characteristic borders of PG (17).

Table 2

| Major criteria |

| Biopsy of ulcer edge demonstrating neutrophilic infiltrate |

| Minor criteria (>4) |

| Exclusion of infection |

| Pathergy |

| History of inflammatory bowel disease or inflammatory arthritis |

| History of papule, pustule, or vesicle ulcerating within 4 days of appearing |

| Peripheral erythema, undermining border, and tenderness at ulceration site |

| Multiple ulcerations, at least 1 on an anterior lower leg |

| Cribriform or “wrinkled paper” scar(s) at healed ulcer sites |

| Decreased ulcer size within 1 month of initiating immunosuppressive medication(s) |

PG treatment goals include suppressing the inflammatory process, promoting wound healing, treating superimposed infection, and controlling pain (9,18-23) (Table 3). Treatment response to systemic corticosteroids is usually observed within 48 hours with flattening of the ulcer’s raised borders and formation of granulation tissue (8). However, therapy duration is 4.7 months on average due to slow healing (24). PG scars can be significant if diagnosis is delayed (25,26), and surgical revision including skin grafting or flap reconstruction has been successfully performed under steroid coverage (6,27).

Table 3

| Anti-inflammatory |

| Steroids |

| Indolent or limited disease: topical triamcinolone or tacrolimus applied to the edge of the area twice per week |

| Extensive disease: oral prednisone (1 mg/kg/day) or IV methylprednisolone (0.5–1 mg/kg/day) with taper |

| Steroid-sparing agents |

| Cyclosporine, tacrolimus, cyclophosphamide, colchicine, dapsone, mycophenolate mofetil, methotrexate, thalidomide, IV immune globulin, azathioprine, infliximab, etanercept, adalimumab |

| Wound healing |

| Avoid further trauma/debridement |

| Wound care nursing |

| Extracellular matrix for support |

| Negative pressure dressing |

| Hyperbaric oxygen |

| Pain management |

| Prescription-strength opioids |

| Treating infection |

| Application of topical antibacterial agents |

IV, intravenous.

Red breast syndrome (RBS)

RBS is a non-infectious, self-limited inflammatory entity first described in 2010 in patients undergoing breast reconstruction with an acellular dermal matrix (ADM), a soft connective tissue graft generated by a decellularization process. RBS presents with erythema blanching with pressure overlying the ADM, usually involving the lower pole of the breast, days to weeks after reconstruction (28). RBS incidence may be as high as 7.6% (29) and has been reported rarely with synthetic mesh implantation (28,30).

The exact etiology is uncertain but hypotheses include a delayed type IV allergic reaction to the ADM (28), residual DNA or preservative agents within the ADM, response to vascularization of the ADM, interruption of lymphatic flow due to ADM placement, and hydrolysis of the implanted ADM (30,31). Risk factors include body mass index (BMI) >30 kg/m2, larger breast size, smoking, and axillary dissection (32).

RBS is self-limiting and requires only conservative management but can cause anxiety both for the patient and clinician as it can mimic cellulitis or inflammatory breast cancer (32). However, erythema of RBS directly overlies the ADM unlike the diffuse erythema of cellulitis and there is usually, but not always, absence of infectious manifestations such as local tenderness, warmth, fever, or response to antibiotics (26). If there is any doubt regarding possible infection, empiric antibiotic treatment is recommended (28). Biopsy can be considered if inflammatory breast carcinoma is a clinical concern. Of note, radiation recall dermatitis (RRD), a skin toxicity triggered by anticancer treatment in patients previously treated with radiation therapy, is a mimicker of RBS (33). RDD commonly presents as an erythematous patch confined to the previously irradiated area and is treated with steroid therapy (33). Careful history-taking can differentiate the two entities. Other dermatologic conditions presenting as an erythematous patch which have been reported postoperatively on the breast include rare inflammatory disorders like morphea (34-36) (Figure 2), eosinophilic cellulitis (37), and erythema annulare centrifugum (38), which are all treated with topical steroids. Additionally, panniculitis following autologous fat graft reconstruction (39) and dermatomyositis precipitated by surgery which may mimic RBS have been reported (40-42).

Dermatitis

Dermatitis or eczema of the breast is a rare dermatologic sequela of breast surgery presenting as well-demarcated, scaly, erythematous lesions (43,44) (Figure 3). Numerous mechanisms underlying postsurgical dermatitis have been proposed, including transient intraoperative ischemia due to retractor use leading to decreased skin barrier function, increased postoperative skin tension, and disruption of blood vessels or lymphatic channels during surgery, all predisposing the skin to eczematous changes (43,45).

Treatment consists of low-to-mid-potency topical steroids with improvement expected in 2–4 weeks (43). Mupirocin ointment may be added for suspected impetiginization (43). The presence of similar lesions outside the breast area suggests a diagnosis of tinea corporis, treated with topical antifungal medication. In the case of non-resolving lesions despite therapy, biopsy is warranted to rule out cutaneous metastases, local recurrence. If the nipple-areola complex is affected with non-resolving dermatitis, Paget’s disease (PD) and a diagnostic biopsy should be considered (46). PD is characterized by crusted, scaly, or ulcerated lesions and is often associated with an underlying carcinoma (46). Dermatitis may also mimic allergic contact dermatitis to nipple tattoo dye (47), bandages, tape or topical medication (43), or irritant contact dermatitis to various materials like vacuum-based perioperative external tissue expanders or intraoperative iodine use (48,49), which are more likely to present with erythematous vesicles and crusting. Both are treated with removal of the causative agent and topical steroids.

Burn

In the last several decades a new complication of breast reconstruction has been described in 38 cases: partial- and full-thickness burns. This clinical entity presents with painful erythema and edema with progression to blistering and pallor, sometimes with necrosis in the operated area with sparing of surrounding skin (50). It has been reported to occur 2 months–5 years after surgery, but occurs more frequently during the first year (50). Most cases have been reported after transverse rectus abdominis flap reconstruction both at the recipient and donor site (50).

Iatrogenic changes to sensory and thermoregulatory nerves in the reconstructed breast skin of these cases are thought to lead to the inability to detect painful stimuli or dissipate heat, increasing the risk for burns (50). Most cases occur following solar radiation to the area but burns following thermal radiation from postoperative warming lights, heating pads, sunlamps, hairdryers, electric curlers, and hot dishes have been described (50). In such cases, obtaining a pertinent clinical history is crucial in differentiating burns from mimickers including RBS or erysipelas. Therapy for burns includes conservative treatment with dressings or surgical debridement and flap or graft repair in more severe cases (50). Antibiotics may be administered in cases with overlying infection (51).

Keloids

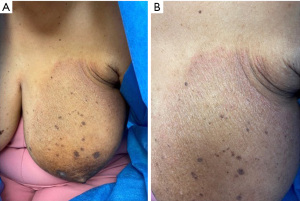

Keloids are common pathological scars that grow beyond the boundary of the original wound into surrounding healthy skin with an erythematous leading edge (52). Keloids are often with pruritic, cosmetically distressing, and can be painful and reduce quality of life (53). Pathogenesis is thought to be related to overactivation of fibroblasts via chronic overexpression of TGF-β isoforms expressed in the normal wound healing process (52). On histopathology, fibroblasts and excessive accumulation of collagen are seen (52).

Unlike hypertrophic scars that can heal spontaneously, keloids commonly progress to form thick, firm scars (52). Therapeutic modalities include intralesional steroid or 5-fluorouracil injections, silicone gel or sheets, topical therapies including tacrolimus and imiquimod, cryotherapy, surgery, and adjunctive radiation or laser treatment (52). Importantly, there have been rare reports of cutaneous breast cancer metastases mimicking keloids on the chest wall (54). While treatment frequently yields variable results, lesions that fail to respond to therapy may be suggestive of primary or metastatic carcinoma recurrence. Additionally, keloid-like lesions presenting more than 3 months postoperatively, outside of scars, and those with an atypical appearance should alert clinicians to the possibility of malignancy and prompt a diagnostic biopsy (54).

Infectious

Surgical site infection (SSI)

SSIs can be classified as superficial wound infections involving skin or subcutaneous tissue, deep wound infections extending into the fascial and muscle layers, or periprosthetic infection, and present with redness, delayed healing, fever, pain, tenderness, warmth, or swelling.

Risk for SSI is increased with higher BMI, diabetes mellitus, smoking, or concomitant active skin disorders, advanced tumor clinical stage, and neoadjuvant radiotherapy which is known to impair wound healing (55). Breast-conserving operations are less frequently associated with SSI than radical procedures like mastectomy or mastectomy with immediate reconstruction (55). In breast cancer patients undergoing prosthesis-based breast reconstruction risk factors for developing infection include smoking, chemotherapy, and skin necrosis following prior mastectomy (56). As mentioned, PG and RBS may mimic SSI.

Superficial SSIs are treated with wound irrigation, dressing changes, and oral antibiotics, while deep SSIs require surgical debridement and aggressive intravenous antibiotic therapy (55,57). In the case of periprosthetic infection, device salvage may be attempted using a combination of systemic antibiotics combined with antibiotic lavage, capsule curettage, capsulectomy, and device exchange with or without postoperative continuous antibiotic irrigation (56).

Herpes zoster

Herpes zoster, or shingles, is the reactivation of latent varicella-zoster virus in the dorsal root ganglia that follows primary infection earlier in life. Up to 1 million people in the United States are affected annually (58). Herpes zoster presents as a tender, erythematous, vesicular or pustular rash in a dermatomal distribution with a painful prodrome in the affected area. Postherpetic neuralgia, a condition presenting with intense pain persisting more than 3 months after rash resolution, is a complication of up to 70% of untreated herpes zoster patients (58). Risk factors for reactivation include old age and immunosuppression with chemotherapy (58) in breast cancer patients (59).

In postsurgical breast cancer patients presenting with zosteriform rash, more insidious diagnoses of cutaneous metastasis or disseminated herpes zoster should also be considered (58,59). When rash presents with firm papules or nodules rather than vesicles or does not resolve with treatment, malignancy may be suspected and a biopsy is indicated for diagnosis (59). Disseminated herpes zoster, a generalized form of zoster necessitating hospitalization given potential for visceral involvement, affects multiple dermatomes and crosses the midline, unlike herpes zoster and is more common in immunosuppressed patients (58). In disseminated zoster, lesions may appear nodular with chronic crusting, in which case polymerase chain reaction testing on active lesion scrapings can be helpful for diagnosis (59). Of note, iatrogenic nerve displacement during breast surgery can lead to loss of the characteristic dermatomal distribution.

Treatment for herpes zoster includes 7 days of oral valacyclovir 1,000 mg 3 times daily, famciclovir 500 mg 3 times daily, or acyclovir 800 mg 5 times daily (59). Observation is also an option in uncomplicated patients presenting 72 hours after rash onset with no progression (59). In patients with suspected disseminated zoster or with progression after 2–3 days of oral therapy should be hospitalized and treated with intravenous acyclovir (59).

Lymphedema-associated dermatoses

Lymphedema

Lymphedema is a common, progressive condition in breast cancer patients characterized by swelling, stiffness, and neuropathy of the affected limb due to excess extracellular protein-rich fluid accumulation presenting on average 2 years after surgery, with progression up to 11 years later to a chronic phase with irreversible intradermal fibrosis with pitting edema, hyperkeratosis, and increased tissue firmness (60). Lymphedema can also involve the breast (61). Axillary surgery and radiotherapy are risk factors with similar rates of disease regardless of sentinel lymph node biopsy or more invasive axillary lymph node dissection (61,62). Differential diagnosis can include various causes of fluid overload including heart, renal, or hepatic failure infection, as well as recurrent malignancy or vascular abnormalities (62). Early intervention with manual lymphatic drainage, compression garments, and exercise can prevent chronic irreversible disease (60,62,63). Surgical techniques to improve lymphatic circulation, such as lymphaticovenous anastomosis and vascularized lymph node transfer, have recently gained popularity (60,62). Lymphedema lowers patient quality of life due to cosmetic disfigurement, lack of mobility, and cost associated with decompressive treatment (60). Additionally, due to impaired immune function in the affected limb, lymphedema patients are at higher risk of developing cutaneous diseases in the affected limb, discussed in further detail below (64).

Erysipelas

Erysipelas is an acute bacterial infection of the dermis, presenting with fever and tender erythematous, edematous plaques with sharply-demarcated margins that spread rapidly, caused most commonly by group A beta-hemolytic streptococci (65,66). There is a well-documented association of erysipelas and lymphedema in postsurgical breast cancer patients resulting in recurrent inflammatory episodes which further damage lymphatic vessels of the affected arm increasing lymphedema severity and risk for future erysipelas infections (67). Additionally, the high protein content of the excess interstitial fluid is an ideal culture medium for bacterial growth (67). Obesity exacerbates risk of infection (68).

Erysipelas is clinically diagnosed based on rash appearance (65). A portal of entry for infection is not always identifiable on exam or based on patient history (68). Of note, erysipelas findings are sometimes described with a peau d’orange appearance, which can mimic inflammatory breast cancer (66). The lesion should be biopsied to rule out malignancy if there is no resolution following therapy. Mild cases of early erysipelas can be treated on an outpatient basis with oral penicillin monotherapy, with broader antibiotic coverage if clinical findings make exclusion of acute cellulitis difficult (66). Macrolides and clindamycin can be used in penicillin-allergic individuals (66). The average duration of antibiotic therapy is 15 days, and up to 21 days in subjects with comorbidities (68). Prophylactic antibiotic therapy in patients with lymphedema is not recommended (63), however recent data suggest that liposuction can significantly reduce erysipelas incidence in postmastectomy lymphedema patients (69). Additionally, trauma, excessive heat, constrictive clothing, exaggerated exercise, and weight gain should be avoided (66).

Cutaneous angiosarcoma (CAS)

CAS, also known as Stewart Treves syndrome, is a rare, aggressive angiosarcoma that develops in patients with chronic lymphedema, most commonly in breast cancer patients treated with radical mastectomy. It presents at first with subtle, poorly circumscribed erythematous lesions that over time coalesce into purpuric and erythematous macules and nodules which may ulcerate or bleed on the affected extremity. Metastatic disease is frequent, particularly in local lymph nodes and lungs (70). The average time of development after radical mastectomy is 12.5 years (71). CAS is recurrent, invasive, and commonly causes death within 1–2 years (71).

CAS pathogenesis is not yet elucidated; however malignant cells are thought to derive from blood vascular or lymphatic endothelial cells (72). Histologically, CAS appearance varies but generally shows numerous irregular vascular channels splitting dermal collagen sometimes with spindle-shaped, polygonal, epithelioid and primitive round cells and increased mitotic activity (70). Immunohistochemical staining for CD34, CD31, ERG, factor VIII, type IV collagen, C-MYC gene amplification can be helpful in diagnosis (70).

There are several mimickers of CAS including the more recently described post-radiation CAS, which differs from CAS by its shorter latency of 6 years post-lumpectomy, lack of association with lymphedema, and consistent location in the radiation field. Lymphangioma circumscriptum, presenting as erythematous deep seated vesicles described as resembling frog spawn, has been reported in postmastectomy lymphedema and may mimic CAS (71). Additionally, sarcoid reaction (73) presenting on the post-mastectomy arm with red papules and nodules, or siliconomas (74) presenting as pink nodules secondary to breast implant rupture have been reported and may mimic angiosarcoma.

There are no standardized management guidelines, but wide local excision and postoperative radiation to decrease the risk of recurrence is most common (70,75). Drugs that target VEGF signaling, as well as new cytotoxic anticancer drugs including denibulin or trabectedin show promise (75).

Neutrophilic dermatosis on site of lymphedema

Neutrophilic dermatosis on the site of postmastectomy lymphedema has been reported in 12 cases in women aged 39–75 years (76). It presents as multiple painful, tender, erythematous papules, which may coalesce to form irregular sharply bordered plaques, sometimes with blisters (76). Unlike the classic neutrophilic dermatosis, Sweet syndrome, systemic symptoms and neutrophilic leukocytosis are mild or absent, relapses are less common, and lesions are restricted to arm affected by lymphedema and resolve without scarring (76,77). Onset from time of breast surgery and cutaneous disease onset ranges from a few months to several years (76). Biopsy reveals a dense infiltrate primarily composed of neutrophils and localized in the dermis (76,78). Pathogenesis is thought to be related to local cytokine accumulation or increased antibody deposition due to inadequate lymphatic draining attracting neutrophils to a site of altered immunocompetence (76).

The differential diagnosis includes other entities presenting with erythematous nodules or plaques including erysipelas, folliculitis, herpes zoster, contact dermatitis, or cutaneous metastases, which can be differentiated via clinical course and biopsy findings (77,78). Treatment includes systemic antibiotics or corticosteroids, or potassium iodide, but disease may also spontaneously remit (77,78).

Delayed breast cellulitis (DBC)

DBC is a newly reported complication of breast conserving therapy with an incidence of up to 12% (79-81). It presents with diffuse breast erythema, edema or peau d’orange, tenderness, and slight warmth, sometimes with improvement after laying, occurring at least 3 months after surgery. Unlike acute cellulitis, DBC has a lower incidence of systemic symptoms, is more insidious, and recurs in up to 22% of patients (79,81). Arm lymphedema and removal of >5 axillary lymph nodes, as well as seroma or hematoma aspiration, obesity, and higher stage cancer are associated with higher risk of DBC (81-83).

It is not yet clear whether DBC is primarily of infectious or inflammatory etiology. DBC may be caused by bacterial infection in the setting of impaired lymphatic drainage (84,85), particularly given reports associating DBC with known sources of infection (86). Others suggest a cyclic inflammatory reaction to protein exudate in patients with lymphedema causes DBC as indicated by the rare isolation of pathogens and lack of constitutional symptoms in most cases (81,87).

The differential diagnosis importantly includes inflammatory breast cancer, which also presents with an edematous and erythematous breast but can be definitively diagnosed via biopsy. Other mimickers of DBC presenting with an erythematous breast include reticular telangiectatic erythema due to non-absorbable suture (88), as well as foreign body reaction to due inadvertent reversed placement of ADM that resolved with ADM removal (89). Finally, squamous cell carcinoma of the implant capsule following reconstruction has been reported and can mimic the clinical course of DBC (90).

Optimal treatment is debated, as some authors find complete resolution with 10–14 days of empiric antibiotic therapy (91), while other have found that most cases resolved without antibiotic treatment (79). As noted previously, patients should be educated regarding lymphedema precautions so that chronic fibrotic skin changes and DBC risk may be minimized (82). If the condition persists after 4 months of antibiotic therapy, a biopsy should be performed to rule out malignancy (87); however mean time to resolution of symptoms has been described to be 7.5 months (79).

Conclusions

Surgical resection of malignancy and breast reconstruction in breast cancer patients can result in many dermatologic sequalae affecting the breast and ipsilateral limb. It is crucial that healthcare practitioners are aware of relevant cutaneous changes to appropriately diagnose or rule out infection or malignancy and obtain timely treatment to improve patient outcomes and quality of life. Our review supports the need for further investigations to define the etiology and optimal treatment of RBS and DBC, as well as effective angiosarcoma treatment.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the Narrative Review reporting checklist. Available at https://abs.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/abs-22-39/rc

Peer Review File: Available at https://abs.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/abs-22-39/prf

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://abs.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/abs-22-39/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. Written informed consent was obtained from the patients for the publication of this article and accompanying images.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Ahmad A. Breast Cancer Statistics: Recent Trends. Adv Exp Med Biol 2019;1152:1-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Miller AM, Steiner CA, Barrett ML, et al. Breast Reconstruction Surgery for Mastectomy in Hospital Inpatient and Ambulatory Settings, 2009–2014. In: Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Briefs [Internet]. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US), 2006.

- Billings SD, McKenney JK, Folpe AL, et al. Cutaneous angiosarcoma following breast-conserving surgery and radiation: an analysis of 27 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 2004;28:781-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Serletti JM, Fosnot J, Nelson JA, et al. Breast reconstruction after breast cancer. Plast Reconstr Surg 2011;127:124e-35e. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Milam EC, Rangel LK, Pomeranz MK. Dermatologic sequelae of breast cancer: From disease, surgery, and radiation. Int J Dermatol 2021;60:394-406. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kim D, Hur SM, Lee JS, et al. Pyoderma Gangrenosum Mimicking Wound Infection after Breast Cancer Surgery. J Breast Cancer 2021;24:409-16. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hicks MI, Garton KJ, Bitterly TJ. Pyoderma gangrenosum in the setting of reconstructive breast surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol 2010;62:AB36.

- Leppard WM, Reynolds MF, Schimpf DK, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum of the breast after bilateral simple mastectomies for ductal carcinoma in situ. Am Surg 2011;77:E144-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tamer F, Adışen E, Tuncer S, et al. Surgical treatment of pyoderma gangrenosum following deep inferior epigastric perforator flap breast reconstruction. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adriat 2016;25:55-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hammond D, Chaudhry A, Anderson D, et al. Postsurgical Pyoderma Gangrenosum After Breast Surgery: A Plea for Early Suspicion, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Aesthetic Plast Surg 2020;44:2032-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shiba-Tokuchi K, Moriuchi R, Morita Y, et al. Ulceration on an old cervical operative scar: Post-surgical pyoderma gangrenosum induced by recent mastectomy. J Dermatol 2017;44:e244-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rajapakse Y, Bunker CB, Ghattaura A, et al. Case report: pyoderma gangrenosum following Deep Inferior Epigastric Perforator (Diep) free flap breast reconstruction. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 2010;63:e395-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Guaitoli G, Piacentini F, Omarini C, et al. Post-surgical pyoderma gangrenosum of the breast: needs for early diagnosis and right therapy. Breast Cancer 2019;26:520-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Maverakis E, Ma C, Shinkai K, et al. Diagnostic Criteria of Ulcerative Pyoderma Gangrenosum: A Delphi Consensus of International Experts. JAMA Dermatol 2018;154:461-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shirahama S, Furukawa F, Takigawa M. Recurrent pemphigus vulgaris limited to the surgical area after mastectomy. J Am Acad Dermatol 1998;39:352-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Khurana M, Torbeck R, Kauh Y. An atrophic plaque on the breast six years after breast reconstruction surgery. Dermatol Online J 2016;22:13030/qt2zt690tx.

- Salhab M, Al Sarakbi W, Mokbel K. Skin and fat necrosis of the breast following methylene blue dye injection for sentinel node biopsy in a patient with breast cancer. Int Semin Surg Oncol 2005;2:26. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Suzuki Y, Yokoyama K, Terao M, et al. Pyoderma Gangrenosum after Breast Mastectomy and Primary Rectus Abdominis Flap Reconstruction. Tokai J Exp Clin Med 2017;42:133-8. [PubMed]

- Reddy R, Favreau T, Stokes T, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum following breast reconstructive surgery: a case report of treatment with immunosuppression and adjunctive xenogeneic matrix scaffolds. J Drugs Dermatol 2011;10:545-7. [PubMed]

- Simpson J, Harris P, Stamp G, et al. A case series of pyoderma gangrenosum after deep inferior epigastric perforator-flap breast reconstruction. Br J Dermatol 1951;171:19-20.

- Pellegrino SA, Cham A, Pitcher M. Pyoderma gangrenosum of the breast 17 years after breast cancer treatment. BMJ Case Rep 2020;13:e232983. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Li WY, Andersen JC, Jung J, et al. Pyoderma Gangrenosum After Abdominal Free Tissue Transfer for Breast Reconstruction: Case Series and Management Guidelines. Ann Plast Surg 2019;83:63-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Patel DK, Locke M, Jarrett P. Pyoderma gangrenosum with pathergy: A potentially significant complication following breast reconstruction. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 2017;70:884-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ehrl DC, Heidekrueger PI, Broer PN. Pyoderma gangrenosum after breast surgery: A systematic review. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 2018;71:1023-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Caterson SA, Nyame T, Phung T, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum following bilateral deep inferior epigastric perforator flap breast reconstruction. J Reconstr Microsurg 2010;26:475-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schoemann MB, Zenn MR. Pyoderma gangrenosum following free transverse rectus abdominis myocutaneous breast reconstruction: a case report. Ann Plast Surg 2010;64:151-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- García-Ruano AA, Deleyto E, Lasso JM. First Report of Pyoderma Gangrenosum after Surgery of Breast Cancer-Related Lymphedema with Transfer of Vascularized Free Lymph Nodes of the Groin and Simultaneous DIEP Flap. Breast Care (Basel) 2016;11:57-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mayer HF, Perez Colman M, Stoppani I. Red breast syndrome (RBS) associated to the use of polyglycolic mesh in breast reconstruction: a case report. Acta Chir Plast 2020;62:50-2. [PubMed]

- Ganske I, Hoyler M, Fox SE, et al. Delayed hypersensitivity reaction to acellular dermal matrix in breast reconstruction: the red breast syndrome? Ann Plast Surg 2014;73:S139-43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tsuji W, Yotsumoto F. Pros and cons of immediate Vicryl mesh insertion after lumpectomy. Asian J Surg 2018;41:537-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Danino MA, El Khatib AM, Doucet O, et al. Preliminary Results Supporting the Bacterial Hypothesis in Red Breast Syndrome following Postmastectomy Acellular Dermal Matrix- and Implant-Based Reconstructions. Plast Reconstr Surg 2019;144:988e-92e. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ball JF, Sheena Y, Tarek Saleh DM, et al. A direct comparison of porcine (Strattice™) and bovine (Surgimend™) acellular dermal matrices in implant-based immediate breast reconstruction. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 2017;70:1076-82. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bhangoo RS, Cheng TW, Petersen MM, et al. Radiation recall dermatitis: A review of the literature. Semin Oncol 2022;49:152-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Moretti A, Bianchi F, Abbate IV, et al. Localized morphea after breast implant for breast cancer: A case report. Tumori 2018;104:NP25-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chiriac A, Podoleanu C, Coros MF, et al. Localized Morphea Developing in a Scar After Breast Carcinoma Surgery in the Absence of Radiotherapy. J Cutan Med Surg 2016;20:606. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sethu C, Wong KY, Slade-Sharman D. Morphea masquerading as cellulitis. BMJ Case Rep 2019;12:e230816. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ferreli C, Pinna AL, Atzori L, et al. Eosinophilic cellulitis (Well's syndrome): a new case description. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 1999;13:41-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ko WC, You WC. Erythema annulare centrifugum developed post-breast cancer surgery. J Dermatol 2011;38:920-22. [PubMed]

- Logunova V, Bridges AG. Subcutaneous mixed lobular and septal panniculitis with numerous eosinophils associated with autologous fat grafting: Expanding the differential diagnosis of eosinophilic panniculitis. J Cutan Pathol 2020;47:305-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Otsuka Y, Watanabe H, Kano Y, et al. Occurrence of Dermatomyositis Immediately after Mastectomy Subsequent to Severe Chemotherapeutic Drug Eruption. Intern Med 2017;56:3379-83. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wong DE, Williams E, Warrier S. Dermatomyositis Developing Post Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy and Lumpectomy. R I Med J (2013) 2018;101:34-6. [PubMed]

- Abraham Z, Rozenbaum M, Glück Z, et al. Fulminant dermatomyositis after removal of a cancer. J Dermatol 1992;19:424-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rosen AC, Goh C, Lacouture ME, et al. Post-reconstruction dermatitis of the breast. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 2017;70:1369-76. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rzepecki AK, Wang J, Urman A, et al. Nummular eczema of the breast following surgery and reconstruction in breast cancer patients. Acta Oncol 2018;57:1586-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Iwahira Y, Nagasao T, Shimizu Y, et al. Nummular Eczema of Breast: A Potential Dermatologic Complication after Mastectomy and Subsequent Breast Reconstruction. Plast Surg Int 2015;2015:209458. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sandoval-Leon AC, Drews-Elger K, Gomez-Fernandez CR, et al. Paget's disease of the nipple. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2013;141:1-12. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Goossens A, Verhamme B. Contact allergy to permanent colorants used for tattooing a nipple after breast reconstruction. Contact Dermatitis 2002;47:250. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Uda H, Sugawara Y, Sarukawa S, et al. Brava and autologous fat grafting for breast reconstruction after cancer surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg 2014;133:203-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Johnston DB, Irwin GW, McGeown E, et al. Use of additional absorbent pad in the skin preparation and draping of breast patients to reduce rates of contact dermatitis. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2015;97:615. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Delfino S, Brunetti B, Toto V, et al. Burn after breast reconstruction. Burns 2008;34:873-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Price RK, Mokbel K, Carpenter R. Hot-water bottle induced thermal injury of the skin overlying Becker's mammary prosthesis. Breast 1999;8:141-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Betarbet U, Blalock TW. Keloids: A Review of Etiology, Prevention, and Treatment. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol 2020;13:33-43. [PubMed]

- Lee HJ, Jang YJ. Recent Understandings of Biology, Prophylaxis and Treatment Strategies for Hypertrophic Scars and Keloids. Int J Mol Sci 2018;19:711. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mullinax K, Cohen JB. Carcinoma en cuirasse presenting as keloids of the chest. Dermatol Surg 2004;30:226-8. [PubMed]

- Angarita FA, Acuna SA, Torregrosa L, et al. Perioperative variables associated with surgical site infection in breast cancer surgery. J Hosp Infect 2011;79:328-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Reish RG, Damjanovic B, Austen WG Jr, et al. Infection following implant-based reconstruction in 1952 consecutive breast reconstructions: salvage rates and predictors of success. Plast Reconstr Surg 2013;131:1223-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Al-Hilli Z, Wilkerson A. Breast Surgery: Management of Postoperative Complications Following Operations for Breast Cancer. Surg Clin North Am 2021;101:845-63. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tuchman M, Weinberg JM. Monodermatomal herpes zoster in a pseudodisseminated distribution following breast reconstruction surgery. Cutis 2008;81:71-2. [PubMed]

- Al Saud N, Jabbour S, Kechichian E, et al. A Systematic Review of Zosteriform Rash in Breast Cancer Patients: An Objective Proof of Flap Reinnervation and a Management Algorithm. Ann Plast Surg 2018;81:456-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Planinšek Ručigaj T, Tlaker Žunter V. Lymphedema after breast and gynecological cancer - a frequent, chronic, disabling condition in cancer survivors. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat 2015;23:101-7. [PubMed]

- Degnim AC, Miller J, Hoskin TL, et al. A prospective study of breast lymphedema: frequency, symptoms, and quality of life. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2012;134:915-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pappalardo M, Starnoni M, Franceschini G, et al. Breast Cancer-Related Lymphedema: Recent Updates on Diagnosis, Severity and Available Treatments. J Pers Med 2021;11:402. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pereira de Godoy JM, Azoubel LM, Guerreiro Godoy Mde F. Erysipelas and lymphangitis in patients undergoing lymphedema treatment after breast-cancer therapy. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adriat 2009;18:63-5. [PubMed]

- Mallon E, Powell S, Mortimer P, et al. Evidence for altered cell-mediated immunity in postmastectomy lymphoedema. Br J Dermatol 1997;137:928-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- El Saghir NS, Otrock ZK, Bizri AR, et al. Erysipelas of the upper extremity following locoregional therapy for breast cancer. Breast 2005;14:347-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Naveen KN, Pai VV, Sori T, et al. Erysipelas after breast cancer treatment. Breast 2012;21:218-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- von Meyenfeldt M, Lopez Penha TR, Keymeulen KBIM, et al. The incidence of skin infections in breast cancer related lymphedema. EJC Suppl 2010;8:219. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1359634910705693?via%3Dihub

- Korbi A, Hajji A, Dahmani H, et al. Erysipelas on surgical scar: a case report. Pan Afr Med J 2020;35:30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lee D, Piller N, Hoffner M, et al. Liposuction of Postmastectomy Arm Lymphedema Decreases the Incidence of Erysipelas. Lymphology 2016;49:85-92. [PubMed]

- Bernia E, Rios-Viñuela E, Requena C. Stewart-Treves Syndrome. JAMA Dermatol 2021;157:721. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Drachman D, Rosen L, Sharaf D, et al. Postmastectomy low-grade angiosarcoma. An unusual case clinically resembling a lymphangioma circumscriptum. Am J Dermatopathol 1988;10:247-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Goerdt LV, Schneider SW, Booken N. Cutaneous Angiosarcomas: Molecular Pathogenesis Guides Novel Therapeutic Approaches. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 2022;20:429-43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Piccolo V, Russo T, Baroni A. More insights into the immunocompromised district. Int J Dermatol 2014;53:e338-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fernandez KH, Wollner J, Stone MS. Hard, pink nodules on the upper extremities. Peripheral siliconomas. Arch Dermatol 2011;147:1215-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fujisawa Y, Yoshino K, Fujimura T, et al. Cutaneous Angiosarcoma: The Possibility of New Treatment Options Especially for Patients with Large Primary Tumor. Front Oncol 2018;8:46. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- García-Río I, Pérez-Gala S, Aragüés M, et al. Sweet's syndrome on the area of postmastectomy lymphoedema. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2006;20:401-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gutiérrez-Paredes E, González-Rodríguez A, Molina-Gallardo I, et al. Neutrophilic dermatosis on postmastectomy lymphedema. Actas Dermosifiliogr 2012;103:649-51. [PubMed]

- Sherif RD, Harmaty MA, Torina PJ. Sweet Syndrome After Bilateral Deep Inferior Epigastric Perforator Flap Breast Reconstruction: A Case Report. Ann Plast Surg 2017;79:e30-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zippel D, Siegelmann-Danieli N, Ayalon S, et al. Delayed breast cellulitis following breast conserving operation. Eur J Surg Oncol 2003;29:327-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rescigno J, McCormick B, Brown AE, et al. Breast cellulitis after conservative surgery and radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1994;29:163-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Indelicato DJ, Grobmyer SR, Newlin H, et al. Delayed breast cellulitis: an evolving complication of breast conservation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2006;66:1339-46. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Brewer VH, Hahn KA, Rohrbach BW, et al. Risk factor analysis for breast cellulitis complicating breast conservation therapy. Clin Infect Dis 2000;31:654-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mertz KR, Baddour LM, Bell JL, et al. Breast cellulitis following breast conservation therapy: a novel complication of medical progress. Clin Infect Dis 1998;26:481-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Simon MS, Cody RL. Cellulitis after axillary lymph node dissection for carcinoma of the breast. Am J Med 1992;93:543-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hughes LL, Styblo TM, Thoms WW, et al. Cellulitis of the breast as a complication of breast-conserving surgery and irradiation. Am J Clin Oncol 1997;20:338-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Manian FA. Cellulitis associated with an oral source of infection in breast cancer patients: report of two cases. Scand J Infect Dis 1997;29:421-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Staren ED, Klepac S, Smith AP, et al. The dilemma of delayed cellulitis after breast conservation therapy. Arch Surg 1996;131:651-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Armengot-Carbo M, Sabater V, Botella-Estrada R. Reticular telangiectatic erythema: a reactive clinicopathological entity related to the presence of foreign body. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2016;30:194-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Heyer K, Buck DW 2nd, Kato C, et al. Reversed acellular dermis: failure of graft incorporation in primary tissue expander breast reconstruction resulting in recurrent breast cellulitis. Plast Reconstr Surg 2010;125:66e-8e. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Goldberg MT, Llaneras J, Willson TD, et al. Squamous Cell Carcinoma Arising in Breast Implant Capsules. Ann Plast Surg 2021;86:268-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Baddour LM. Breast cellulitis complicating breast conservation therapy. J Intern Med 1999;245:5-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Kost Y, Muskat A, McLellan BN. Postoperative dermatologic sequelae of breast cancer in women: a narrative review of the literature. Ann Breast Surg 2024;8:4.